What Is a Robot? A Beginner’s Guide

| Updatedby RB Team · 6 mins read

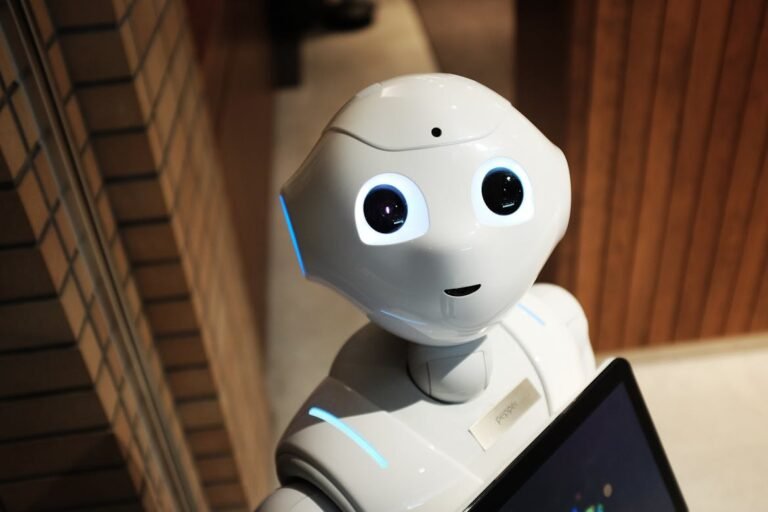

Robots across industries and environments, illustrating how machines sense, compute, and act in the real world – from factory floors and warehouses to autonomous exploration systems.

Robots defy easy categorization. Some glide across factory floors on wheels, others balance on two legs or move with the deliberate gait of four or six. A growing number never touch the ground at all, lifting into the air as autonomous drones or navigating the depths as underwater machines.

They work in radically different worlds. In pristine cleanrooms, robots assemble microchips with microscopic precision; in loud, oil-streaked plants, they weld steel frames day and night.

Some are small enough to disappear into a palm, others loom at the scale of household appliances. A handful flip pancakes or sort groceries. Others travel far beyond human reach, operating in places where people cannot go — from the ocean floor to the surface of Mars.

This extraordinary diversity makes one simple question surprisingly difficult to answer: what exactly is a robot? The term means different things to different people, and even robotics experts do not always agree.

Popular culture and science fiction have further shaped expectations, often associating robots with humanoid forms and human-like intelligence. In reality, robots are far more varied and often far less human-looking.

A Simple Definition of a Robot

Despite the debate, a practical definition helps clarify the basics. A robot is an autonomous machine capable of sensing its environment, processing information to make decisions, and performing actions in the physical world.

This definition captures the essential qualities shared by most robots without being overly restrictive. It includes machines that operate independently, interact with their surroundings, and translate computation into physical action.

A common example is a robotic vacuum cleaner. It uses sensors to detect walls and furniture, computes paths to cover a room efficiently, and acts by moving and cleaning. While simple, it demonstrates the core robotic loop of sensing, computing, and acting.

No definition is perfect, however. By this logic, devices such as dishwashers, elevators, or thermostats could also be considered robots. This ambiguity highlights why robotics remains a field with flexible boundaries rather than strict classifications.

What Makes Something a Robot?

Roboticists often focus less on labels and more on capabilities. While opinions differ, most agree that robots share three fundamental components.

Robots typically can:

- Sense their environment

- Compute or process information

- Act upon the physical world

These components vary widely between robots. Some use simple sensors, such as bump detectors, while others rely on cameras, gyroscopes, and laser scanners. Computation may involve anything from a small control circuit to powerful processors. Actions may include movement, manipulation, or interaction with objects and people.

For example, cruise control in a car senses speed, compares it to a target value, and adjusts acceleration. Some experts consider this a very simple robot, while others do not. As Rodney Brooks famously suggested, defining a robot precisely is often less useful than recognizing one in practice.

How Robots Work

Although robots differ greatly in appearance and function, they all operate according to a similar underlying process. This process is known as a feedback loop.

A robot continuously:

- Collects data from sensors

- Processes that data using computation

- Sends commands to motors or actuators

This loop repeats many times per second, allowing the robot to adjust its behavior in response to changes in the environment. Feedback is what allows robots to appear intelligent, stable, and responsive.

A well-known example is the BigDog quadruped robot developed by Boston Dynamics. BigDog uses sensors to measure joint positions, forces, and body orientation. Its computer calculates how to move its legs to maintain balance, even when walking on rough terrain or being pushed. By constantly updating its actions through feedback, the robot can walk, climb, and recover from disturbances.

Autonomy in Robots

Autonomy is a key concept in robotics, but it exists on a spectrum rather than as a single state. Not all robots operate with the same level of independence.

Robots may be:

- Fully teleoperated by humans

- Partially autonomous with human supervision

- Fully autonomous with minimal or no human input

Many real-world robots combine autonomous behavior with remote control, allowing humans to intervene when necessary. This hybrid approach is common in industrial, medical, and exploratory robots.

Because autonomy varies, opinions differ on how much independence a machine needs to be considered a robot. Robotics pioneer Joseph Engelberger once summarized this uncertainty by saying that while defining a robot is difficult, people generally recognize one when they see it.

Why Robotics Is Advancing Now

Robotics has existed for decades, yet widespread everyday robots are only now beginning to emerge. The main reasons for past limitations were cost and complexity.

Robots require sensors, processors, actuators, and software, all of which must work together reliably. These components were historically expensive and difficult to integrate. As robots became more capable, costs rose quickly.

Today, this is changing. Advances in computing, sensing, and artificial intelligence are making robots more affordable and capable. According to Daniela Rus, robotics is entering a new era as machines leave research labs and begin operating in real-world environments.

Progress is especially strong in areas such as:

- Robot vision and perception

- Navigation and mapping

- Learning from data and experience

- While challenges remain, the pace of improvement is accelerating.

The Role of AI in Robotics

Modern robotics increasingly relies on artificial intelligence. AI helps robots recognize objects, understand environments, and adapt to new situations. Learning-based approaches allow robots to improve performance over time rather than relying solely on fixed rules.

Robotics software platforms are also becoming more standardized. Shared frameworks and open ecosystems allow developers to build on existing tools rather than starting from scratch. This shift enables faster innovation and more reliable systems.

As hardware becomes cheaper and software more powerful, robots are moving closer to becoming practical, helpful machines in everyday life.

The Future of Robots

The question many people still ask is simple: where are all the robots promised by science fiction? The answer is that robotics is progressing steadily, but real-world complexity makes rapid breakthroughs difficult.

However, momentum is clearly building. Robots are becoming more capable, more affordable, and more useful across industries. As technology continues to improve, robots will increasingly assist humans rather than replace them, handling tasks that are dangerous, repetitive, or inefficient.

Ultimately, the future of robotics depends on people. More engineers, designers, and researchers are needed to build the next generation of robots. And perhaps one day, one of them will finally build a robot that does the laundry.